Medieval libraries (ca. 500 – ca. 1500 a.d.)

Libraries such as the famous library of Alexandria and the Bibliotheca Palatina in Rome already existed in ancient times, but most of these institutions were lost together with their books at the fall of the Roman Empire. Besides willful plundering and destruction, factors such as cultural transformation and medial change played a role in this demise.

Islands of book culture continued to exist, however, particularly in early monasteries. These formed germinal cells for the slow diffusion of reading and writing throughout the western world during the Middle Ages. The revival of book culture was furthered by the spreading of learning and educational institutions and by technological innovations such as the production of paper as a cheap writing material and ultimately the printing press.

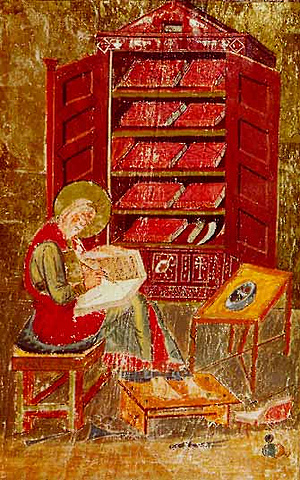

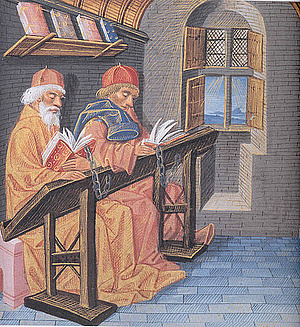

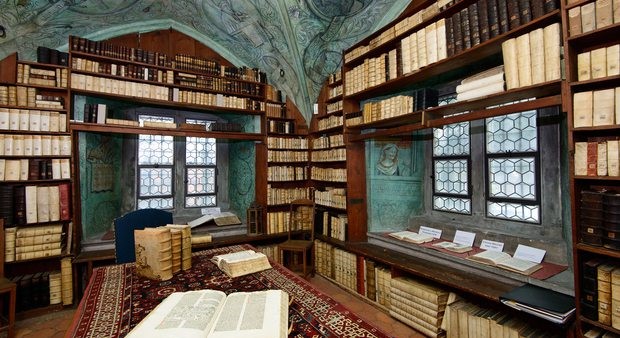

Keeping pace with this development, medieval libraries evolved in their form, content and proliferation. Whereas in the Early Middle Ages books were kept as treasures in an “armarium”, a closed cabinet or chest, in the 13th century with the emergence of universities “librariae” appeared - rooms in which books were not just stored but also read.

Much used volumes lay out on reading desks, often secured with chains. As the size of book collections grew during the Late Middle Ages, books were also often stored on shelves or in bookcases.

Medieval libraries were as a rule presence libraries but in some cases it was possible to lend books off the premises on the basis of a deposit or a written contract.

Besides monasteries and cathedral chapters, now also universities and other educational institutions, churches, hospitals and rectories had their own libraries. Books began to be collected by rulers and members of the nobility, municipal councils, communal authorities, and private scholars. By the end of the Middle Ages, book culture and learning had established itself in Europe to such an extent that it was a key factor in the transition to Early Modernity.

Medieval Library Catalogues and the MBK

Today little remains of the libraries of the Middle Ages in both senses of the word: in most cases neither the buildings nor the book collections exist. Besides provenance notes in individual books with information on their previous owners and origins, catalogues and book lists are the most important sources for our knowledge of the form and content of these lost libraries.

For our purposes, we define “library catalogues” in a very broad sense of the word as “all records presenting a medieval library in whole or in part” (Paul Lehmann, Mittelalterliche Bibliothekskataloge Deutschlands und der Schweiz, Bd. 1: Die Bistümer Konstanz und Chur, Munich 1918; reprint 1969, pp. V–VI). This liberal definition encompasses a correspondingly wide variety of source materials, ranging from catalogues in the narrower sense to inventories of treasures and general inventories, donation and endowment charters, testaments and estates, bills of payment, lending registers, pawn contracts, lists of books written by a certain scribe, etc. These sources may document a book collection in its entirety or only in part. They may be individual documents or transmitted in other source material, such as letters, chronicles or calendars.

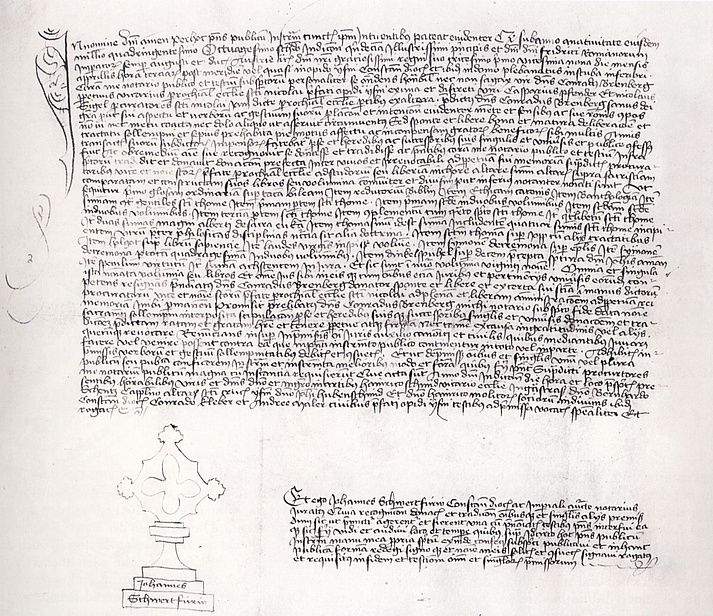

From the library to the edition:

- The Late Medieval parish church library in Isny (above),

- The manuscript donation charter of the parish vicar Konrad Brenberg, 29 April 1482,

- with a list of the books he gave to his parish church library (below).

Such “catalogues” provide us with important information on the composition, size, arrangement and content of medieval libraries. Beyond this they may, depending on their properties, contain additional information, indicating, for example, where the books were collected, in which rooms, and by whom; how the collection originated and what happened to it; who wrote or used the books, and how expensive they were.

In recognition of the intrinsic value of this source material, the project “Medieval Library Catalogues of Germany and Switzerland” (MBK) was founded to compile the existing records and publish them in critical edition. A number of similar national projects to edit medieval library catalogues are running or already completed in Austria, Great Britain and Belgium, while in other countries, such as France, Italy and the Czech Republic, repertories are being compiled.